Three of London’s major institutes, Royal Holloway, the Natural History Museum (NHM) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), have been collaborating on research into how high levels of microplastics are impacting the River Thames, including seriously affecting its inhabitants, the water column and shoreline.

Separate new studies by Postgraduate students Alex McGoran, Katharine Rowley and Katherine McCoy, all from the Department of Biological Sciences at Royal Holloway, reveal that microplastics, are present in high quantities throughout the tidal Thames and are being ingested by wildlife.

Fibres from washing machine outflows and potentially from sewage outfalls, are most commonly ingested by wildlife; but fragments from the breakup of larger plastics, such as packaging items are most abundant in the water. “Flushable” wet wipes were found in high abundance on the shoreline forming huge unsightly reefs. Although pollution from trace metals is now on the decline, the contamination of the Thames by plastic is a major issue.

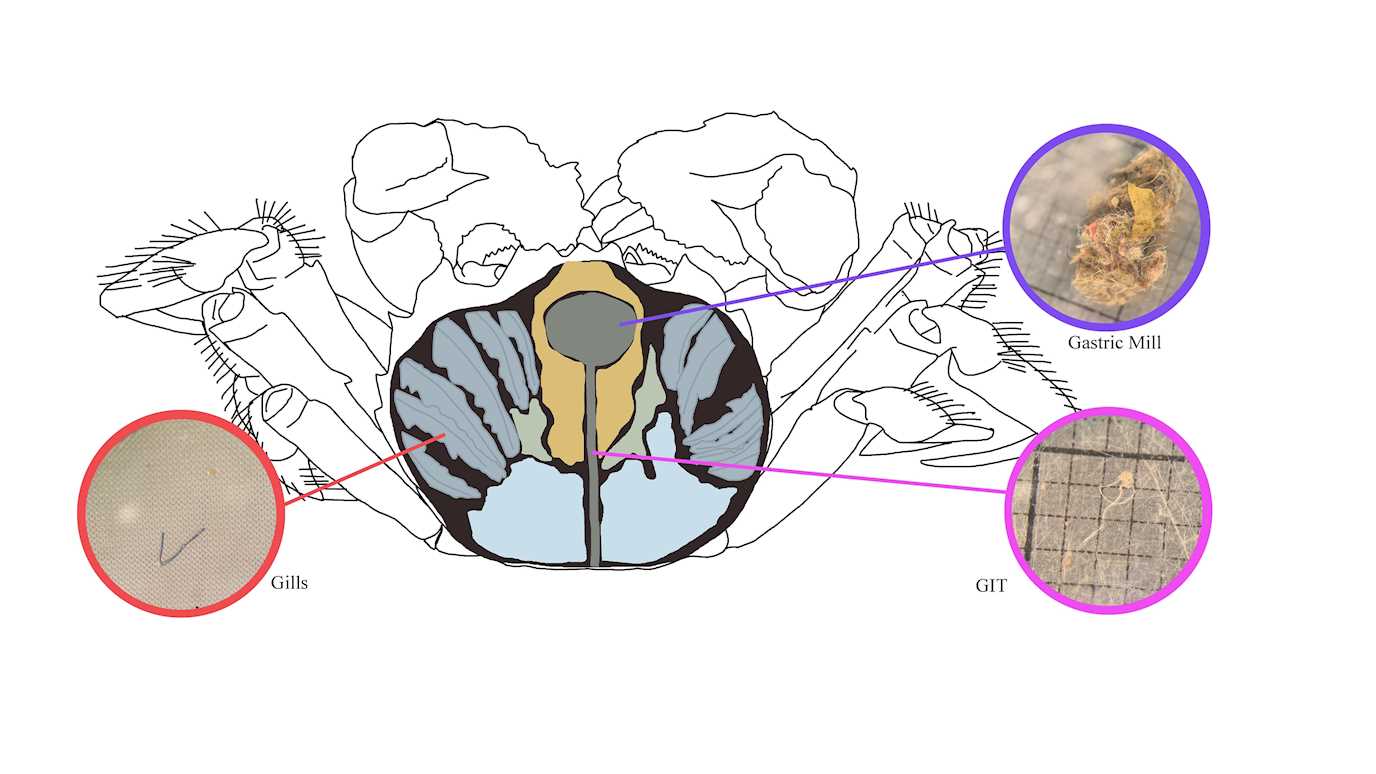

The research of Alex McGoran1, NERC DTP PhD student (Royal Holloway and NHM) and supported by the Fishmongers’ Company Charitable Trust, reports how two resident estuarine species of crab, namely the native shore crab and the invasive Chinese mitten crab, are ingesting microplastics.

In total, 135 crabs were examined and 874 pieces and tangles of plastic, mainly in the form of fibres, were removed for their bodies. Frequently these fibres form tangles comprising up to 100 pieces of plastic and fill the stomach of many crabs which could reduce the urge to feed and leave the animals, with less energy for growth and reproduction.

About 95% of mitten crabs were found to have tangled plastic in the stomach. Although tangles were dominated by fibres, they were found to contain other fragments of microplastics from sanitary pads, balloons, elastic bands and carrier bags.

“Typically, microplastic ingestion is low in many species, with the exception of some groups, such as seabirds. Upon bringing these crabs back to the labs at Natural History Museum, it was shocking to find that they were full of plastic. Tangles of plastic were particularly prevalent in the invasive Chinese mitten crab and we still don’t fully understand the reason for this. We propose that when crabs moult (shedding their exoskeleton to grow) that plastic is trapped in the discarded gut lining”, said Alex McGoran.

Two additional studies into the pollution of the Thames by plastic were undertaken by Masters Students.

Katharine Rowley2 (Royal Holloway, NHM and ZSL) focussed on the quantification of microplastics in the River Thames water column.

Katharine recorded many forms of microplastic in the Thames, ranging from glitter, microbeads to plastic fragments. Her study found that 93.5% of microplastics in the water column were most likely formed from the fragmentation of larger plastic items, with food packaging thought to be a significant source for these plastics.

Her study found high levels of microplastics in the Thames, estimating that on peak ebb tides, 94 thousand microplastics flow down the River Thames per second in some areas. This study highlights the severity of microplastic contamination in the River Thames and the grave need for the reduction of plastic input into the freshwater environment.

Katharine Rowley, said: “Our study provides baseline data for microplastic contamination in the River Thames water column. Globally, in comparison to published estimates of microplastic contamination in marine and freshwater environments, the River Thames contains very high levels of this pollutant, potentially a major input to the North Sea. With the potential threats of plastic pollution to both human and ecosystem health, it is of great importance that the input of plastic into marine and freshwater environments is reduced.”

The research of Katherine McCoy (Royal Holloway and NHM), in collaboration with river clean-up charity, Thames21, looked at “flushable” and “non-flushable” wet wipes as a source of plastic pollution in the River Thames and the environmental impacts they have on the invasive Asian clam. Wet wipes found in sewage effluent are deposited in large numbers on the foreshore on the south bank, just upstream from Hammersmith Bridge, creating massive wet wipe reefs. This study demonstrated that high densities of wet wipes are associated with low population numbers of clams, and vice versa. It was found that clams adjacent to the wet wipe reefs contained synthetic polymers, some of which may have originated from the wet wipe reefs and other pollutants found on the site such as sanitary items.

Katherine McCoy, said: “This research highlights the impacts of improper waste disposal on our environment, especially the flushing of wet wipes. These products are often described as flushable, but they have been known to block sewage pipes by contributing to fatbergs and have now been seen to cause environmental disruption on the foreshores of the river Thames. Our study shows that stricter regulations are needed for the labelling and disposal of these products. There is great scope to further research the impacts of microplastics and indeed microfibres on Thames organisms.”

Professor Dave Morritt from the Department of Biological Sciences at Royal Holloway, said: “Taken together these studies show how many different types of plastic, from microplastics in the water through to larger items of debris physically altering the foreshore, can potentially affect a wide range of organisms in the River Thames.

“The increased use of single-use plastic items, and the inappropriate disposal of such items, including masks and gloves, along with plastic-containing cleaning products, during the current Covid-19 pandemic, may well exacerbate this problem.

“Thames Water has recently reported an increase in wet wipe-related blockages of sewer systems and when the Covid-19 restrictions on fieldwork are lifted, it would be interesting to find out the prevalence of these products in the River Thames.

“We must not forget that, although these studies illustrate the problem on a local scale, plastic pollution is very much a global issue.”

Anna Cucknell, ZSL’s Thames Project Manager, said: “Plastic pollution is devastating for aquatic ecosystems and I was shocked by the densities we found. Our study showed the majority of microplastics in the Thames are created by larger plastic items breaking down which is why the #OneLess campaign, led by ZSL and partners, is working to reduce single use plastic water bottles in London. To date it has eliminated 4.4 million single-use plastic water bottles from London's supply chains and removed 114,000 from the Thames. Thanks to decades of conservation two species of seal and more than 100 species of fish including sharks, seahorses and the Critically Endangered European eel, call the Thames Estuary home. We must not let plastic pollution threaten their survival.”

Dr Paul Clark, Life Sciences Department, NHM said “I was born in London and as a child I remember the Thames as a heavily polluted river which led to the decline of its fish populations. When the Government ordered a clean-up of the catchment the River returned back to life. What our students have shown in this collaboration is that although the Thames is certainly cleaner with regards some chemical pollutants, e.g. heavy metals, the River is severely polluted with plastic. And once again our wildlife is threatened.”