New archaeological research has discovered the oldest human burial in Africa, dating back 78,000 years ago, at a cave site on the Kenyan coast called Panga ya Saidi.

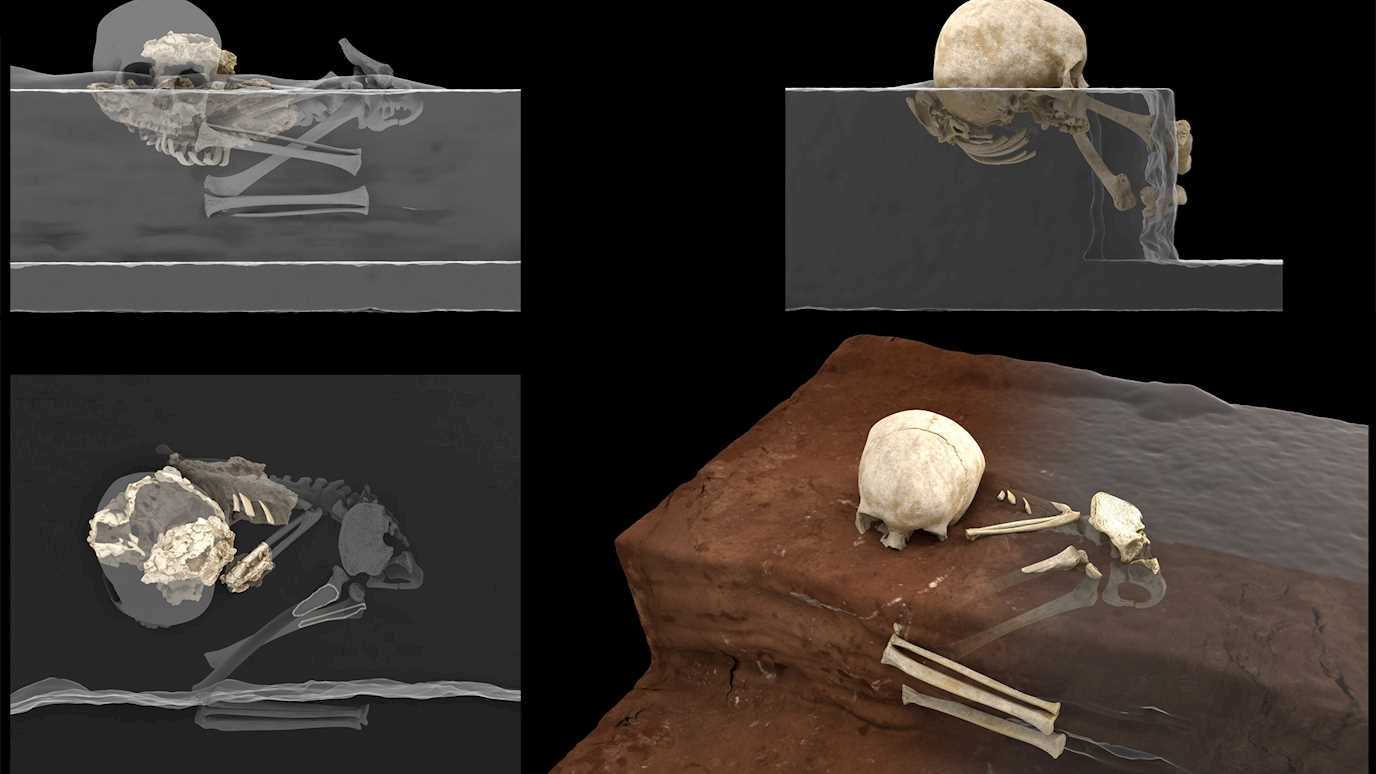

Virtual reconstruction of the Panga ya Saidi hominin remains at the site (left) and ideal reconstruction of the child’s original position at the moment of finding (right) Photo credit: Jorge González/Elena Santos

The international team of scientists, including an academic from Royal Holloway, University of London, found the remains of a 2.5 to 3 year-old child buried in a shallow grave, directly under the sheltered overhang of Panga ya Saidi cave.

The remains - nicknamed ‘Mtoto’ – meaning child in Swahili, reveal how Middle Stone Age populations interacted with the dead. This new discovery has now added to the growing evidence of early complex social behaviours in Homo sapiens.

Despite being the continent of our species’ birth, early evidence of Homo sapiens burials in Africa are scarce and often ambiguous. Therefore, little is known about the origin and development of mortuary practices in Africa.

Panga ya Saidi has been an important site for human origins research since excavations began in 2010 as part of a long-term partnership between archaeologists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the National Museums of Kenya. The team consisted of scientists from research organisations and universities across the world, including Royal Holloway.

Portions of the child’s bones were first found during excavations at Panga ya Saidi in 2013, but it wasn’t until 2017 that the small pit feature containing the bones was fully exposed. About three metres below the current cave floor, the shallow, circular pit contained tightly clustered and highly decomposed bones, requiring stabilisation and plastering in the field.

Once plastered, the cast remains were brought to the National Museum in Nairobi and later to the laboratories of the National Research Centre on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, Spain, for further excavation, specialised treatment and analysis.

Two teeth, exposed during initial laboratory excavation of the sediment block, led the researchers to suspect that the remains could be human. Later work at CENIEH confirmed that the teeth belonged to a 2.5- to 3-year-old human child.

Professor María Martinón-Torres, director at CENIEH, said: “We started uncovering parts of the skull and face, with the intact articulation of the mandible and some un-erupted teeth in place.

“The articulation of the spine and the ribs was also miraculously preserved, even conserving the curvature of the thorax cage, suggesting that it was an undisturbed burial and that the decomposition of the body took place right in the pit where the bones were found.”

Microscopic analysis of the bones and surrounding soil confirmed that the body was rapidly covered after burial and that decomposition took place in the pit. In other words, Mtoto was intentionally buried shortly after death.

Luminescence dating securely places Mtoto at 78,000 years ago, making it the oldest known human burial in Africa. Later interments from Africa’s Stone Age also include young individuals – perhaps signalling special treatment of the bodies of children in this ancient period.

Professor Simon Armitage from the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway, said: “We’re really excited about the team’s findings at Panga ya Saidi. Royal Holloway’s contribution was to use luminescence dating to securely place Mtoto’s remains at 78,000 years ago, making it the oldest known human burial in Africa.

“Luminescence dating measures the amount of time that has passed since sand grains were exposed to sunlight, i.e. since they were buried by overlying material. By measuring thousands of individual grains of sand from samples within the burial pit and surrounding sediments, we were able to determine when Mtoto was buried.”

The human remains were found in archaeological levels with stone tools belonging to the African Middle Stone Age, a distinct type of technology that has been argued to be linked to more than one hominin species.

“The association between this child’s burial and Middle Stone Age tools has played a critical role in demonstrating that Homo sapiens was, without doubt, a definite manufacturer of these distinctive tool industries, as opposed to other hominin species,” notes Dr. Emmanuel Ndiema of the National Museums of Kenya.

Professor Nicole Boivin, principal investigator of the original project and director of the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, said: “As soon as we first visited Panga ya Saidi, we knew that it was special.

“The site is truly one of a kind. Repeated seasons of excavation at Panga ya Saidi have now helped to establish it as a key type site for the East African coast, with an extraordinary 78,000-year old record of early human cultural, technological and symbolic activities.”