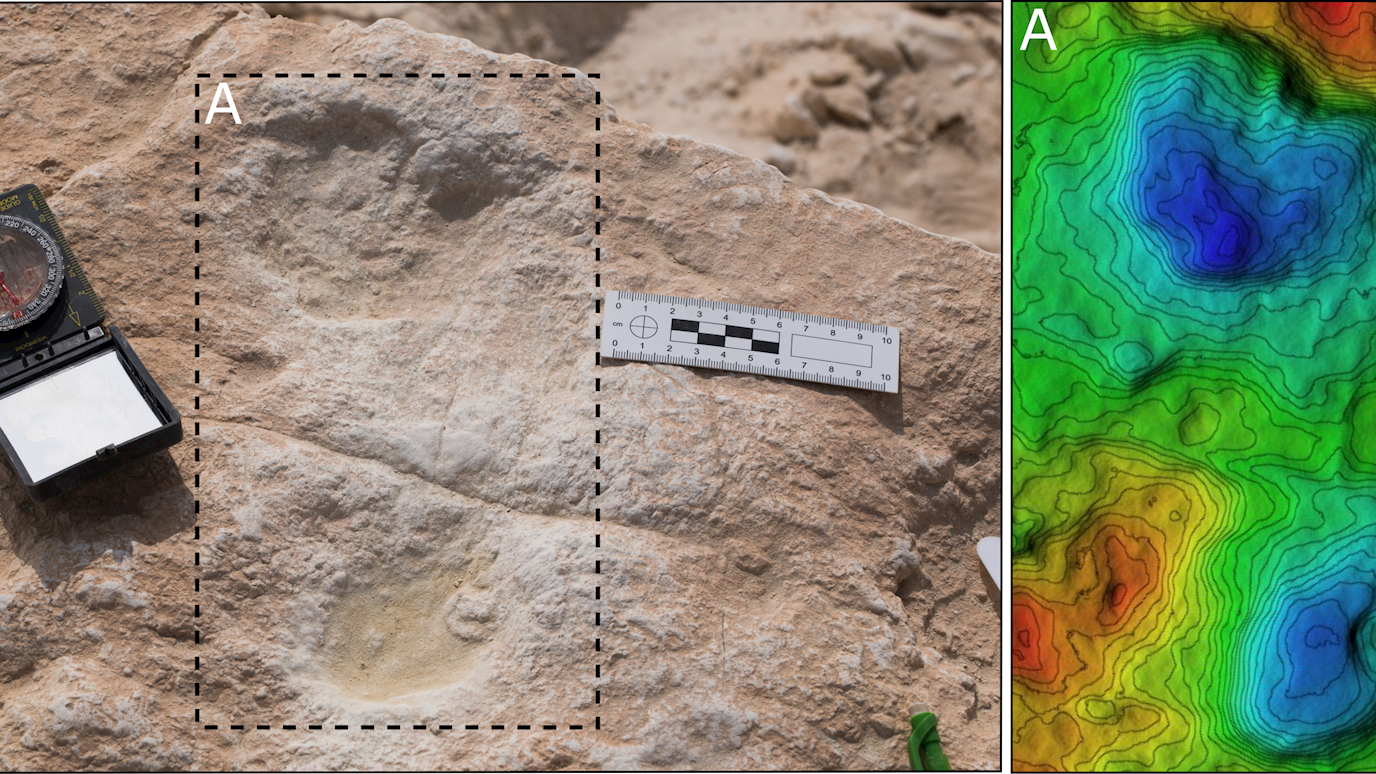

New archaeological research presents the oldest securely dated evidence for humans in Arabia. Discovered in the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia, along with human footprints, the researchers were able to identify footprints also belonging to elephants, horses and camels, which have been exposed following the erosion of overlying sediments.

Researchers from Royal Holloway, the Max Planck Institutes for Chemical Ecology (MPI-CE) and the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH) in Germany, together with a team of international partners, have found a collection of ~120,000 year-old fossilised footprints on the surface of an ancient lakebed in Northern Arabia.

The study, published in Science Advances, provides a key insight into ancient human-animal-environment interactions, while the human footprints provide the earliest evidence for humans on the Arabian Peninsula.

Northern Arabia lies between Africa and Eurasia and is directly south of the only land bridge that connects the two continents. Recent research has demonstrated the humans and other mammals repeatedly dispersed into Northern Arabia during ‘green’ periods, where the current harsh drylands were transformed into lush grasslands littered with freshwater rivers and lakes.

The research team at Royal Holloway was led by PhD student, Richard Clark-Wilson, Professor Ian Candy and Professor Simon Armitage, all from the Department of Geography.

Richard Clark-Wilson from Royal Holloway, said: “At certain times in the past, the deserts that dominate the Arabian Peninsula were transformed into expansive grasslands with permanent freshwater lakes and rivers. When these favourable conditions occurred, the archaeological and fossil records show that human and animal populations migrated together, to inland Arabia.”

Mathew Stewart of MPI-CE, said: “We immediately realised the potential of these findings. Footprints are a unique form of fossil evidence in that they provide snapshots in time, typically representing a few hours or days, a resolution we tend not to get from other records.

“The presence of large animals such as elephants, together with open grasslands and large water resources, may have made Northern Arabia a particularly attractive place to humans moving between Africa and Eurasia.”

The dense concentration of footprints and evidence from the lake sediments suggests that animals may have been congregating around the lake in response to dry conditions and diminishing water supplies.

To find the age of the fossil footprints, researchers from Royal Holloway, dated sand grains buried within the ancient lake deposits.

Professor Simon Armitage from Royal Holloway, explains: “Sand grains act as natural clocks as they record the time elapsed since they were last exposed to sunlight. Once the sands are buried in the lake sediments, they are protected from sunlight and the natural clock begins ticking. We believe that the ancient lake and associated footprints to be about 120,000 years-old.”

Professor Ian Candy from Royal Holloway, said: “The age of the footprints is of interest as they date to a period known as the last interglacial, a time of relatively humid conditions across the region and an important moment in human prehistory. Environmental changes during the last interglacial would have allowed humans and animals to disperse across otherwise desert regions, which normally act as major barriers during the less humid periods, such as today.

“These findings suggest human movements beyond Africa during the last interglacial extended into Northern Arabia, highlighting the importance of this region for the study of human prehistory.”